Dec. 9, 2016

Thesaurus : 02. Lois

June 26, 2015

Publications

Référence complète : Frison-Roche, M.-A., Réguler les "entreprises cruciales", Revista de Direito Mercantil indistrial, econômico e finaceiro, 164/165, Malheiros Editores, 2013, p.19-31.

La publication dans cette revue brésilienne de droit des affaires est une réédition de l'article paru en France.

A première vue, on ne régule que les espaces et l’État n’a pas à pénétrer les entreprises.

Mais l’impératif s’inverse lorsqu’une entreprise absorbe l’espace tout entier, ou lorsqu’elle en a le projet, comme dans le cas

Google. L’entreprise cruciale est négativement celle dont la défaillance entraîne l’effondrement du système; l’entreprise est positivement cruciale si à travers elle le secteur est orienté vers des finalités au service de l’avenir du groupe social.

L’État est alors légitime à pénétrer l’entreprise, pour y faire entendre sa voix, parfois pour y exercer un pouvoir de décision car le dynamisme concurrentiel et le pouvoir de la propriété n’excluent pas la superposition du souci de l’avenir commun, que certains appellent l’intérêt général.

March 16, 2015

Publications

Références complètes : Frison-Roche, Marie-Anne, Les entreprises "cruciales" et leur régulation, in Supiot, Alain (dir.), L'entreprise dans un monde sans frontières. Perspectives économiques et juridiques, coll. "Les sens du droit", Dalloz, 2015, p.253-267.

Même si à première vue l'on ne régule que des espaces, il faut parfois « réguler l’entreprise ». Cela est impératif lorsqu’une entreprise absorbe l’espace tout entier, parce qu’elle est monopolistique ou parce qu’elle a pour projet de devenir le cœur d’un espace crucial, comme l’affirme Google. D’une façon plus générale, il faut repérer les entreprises « cruciales », dont les banques ne sont qu’un exemple, et organiser, au-delà de la supervision, la régulation directe de telles entreprises. Cette régulation doit alors prendre la forme d'une présence de la puissance publique et du Politique à l'intérieur même de l'entreprise, dans l'indifférence de la propriété des titres de capital.

Lire la présentation générale de l'ouvrage dans lequel l'article a été publié.

Accéder à la conférence du 12 juin 2014 et au working paper à partir desquels l'article a été rédigé.

Oct. 23, 2014

Publications

Accéder à la présentation du colloque.

Ce Working paper a servi également de base à un article paru dans la Revue Concurrences.

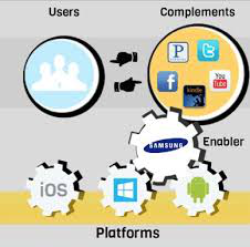

Parce qu'il est difficile de réguler un "marché biface", sauf le temps fugace du contrôle des concentrations, l'idée accessible est de réguler directement l'entreprise qui tire tout son pouvoir de sa position sur une telle structure de marché.

On peut, comme le propose le Conseil d'État, dans son Rapport annuel Le numérique et les droits fondamentaux, considérer que la prise en considération par le droit de cette situation nouvelle doit prendre la forme d'une reconnaissance de la notion de "plateforme", pour l'ériger en catégorie juridique et lui associer une obligation de loyauté, sous la surveillance du régulateur des données personnelles.

L'on peut aussi recourir à une notion plus générale, ici utilisée, d'"entreprise cruciale", à laquelle correspondent des entreprises comme Google, FaceBook, Amazon, etc., parce que ces entreprises remplissent les critères de la définition, à la fois négative et positive de l'entreprise cruciale. La puissance publique est alors légitime, sans que l'État ait à devenir actionnaire, à se mêler de la gouvernance des entreprises et à surveiller les contrats, voire à certifier ceux-ci, comme en finance, sans exiger de l'entreprise ainsi régulée un comportement moral, car ces entreprises privées doivent par ailleurs poursuivre leur fin naturelle constituée par le profit, le développement et la domination, moteur du développement économique. Le développement technologique des plateformes n'en serait pas entravé, tandis que l'aliénation des personnes que l'on peut craindre pourrait être contrée.

Oct. 22, 2014

Thesaurus : 06.1. Textes de l'Union Européenne

Référence complète : Directive 2014/95/UE du Parlement européen et du Conseil du 22 octobre 2014 modifiant la directive 2013/34/UE en ce qui concerne la publication d'informations non financières et d'informations relatives à la diversité par certaines grandes entreprises et certains groupes

July 24, 2014

Publications

At first glance, only areas are regulated and the State doesn't enter private enterprises.

But the imperative is reversed when a company absorbs the entire area, or when a firm has the project to absorb the area, such as Google has. The firm becomes "crucial" and the State must enter the company and intervene.

It is necessary to give the definition of a "crucial firm". A firm is "crucial", in a negative sense, when its failures could cause the collapse of the system; a firm is positively "crucial" if through it the industry is facing the purpose to serve the future of the social group.

The State is then legitimate to enter the company to make its voice heard, sometimes to exercise its decision-making powers.

The competitive dynamism and power of property don't exclude the superimposition of the common concern for the future, which some call the general interest.

June 12, 2014

Conferences

L’expression même d’ « entreprise régulée » peut apparaître comme un contresens : on ne régule qu’un espace qui le requiert en raison de ses défaillances structurelles, et non pas une entreprise qui développe ses activités sur celui-ci. Retour ligne automatique

Mais à la réflexion, il faut parfois « réguler l’entreprise », nécessité qui s’imposera de plus en plus. Cela est impératif lorsqu’une entreprise absorbe l’espace tout entier, parce qu’elle est monopolistique ou parce qu’elle pour projet de devenir le cœur d’un espace crucial, comme l’affirme Google se présentant comme le futur cerveau mondial. D’une façon plus générale, il faut repérer les entreprises « cruciales », dont les banques ne sont qu’un exemple, et organiser, au-delà de la supervision, la régulation directe de telles entreprises.

Cette régulation des entreprises cruciales doit alors prendre la forme d’une présence de la puissance publique et du Politique à l’intérieur de l’entreprise elle-même, afin que l’Etat interfère dans les décisions dont le groupe social subit les conséquences. La régulation peut aller au-delà de la « présence publique », pour prendre la forme du « pouvoir public », l’Etat décidant comme opérateur. Dans de telles conditions de crucialité, la neutralisation de « l’entreprise publique » par le droit de la concurrence doit cesser, l’entreprise publique devant être reconnue comme un instrument de régulation, en distance de la simplicité concurrentielle.

Lire le programme et la présentation de tous les intervenants.

June 2, 2014

Publications

The expression "regulated company" may appear as an oxymoron : the State regulates areas (markets, networks, etc.) because of their structural failures, but the State doesn't enter a company that develops its activities autonomously.

The expression "regulated company" may appear as an oxymoron : the State regulates areas (markets, networks, etc.) because of their structural failures, but the State doesn't enter a company that develops its activities autonomously.But on reflection, it is sometimes necessary to "regulate a company" and this necessity is increasingly imposed. This is imperative if a company absorbs the entire area, because it is a monopoly or because it wants to become the heart of a crucial area, such as Google which has the project to become the future global brain. In a more general way, it is a necessity to locate businesses which are "crucial", banks are only one example, and organize, beyond supervision, providing direct regulation of such firms.

This regulatory power on critical firms must take the form of attendance of public power and policy within the company itself, so that the state interfere in decisions which social group suffers the consequences.

The control can go beyond this "public presence" to take the form of "public authority", the state ruling as operator. Under such conditions of "cruciality", the neutralization of "public enterprise" by the competition law must cease, the public company must be better recognized as a regulatory instrument in distance with the simple game of competition.

May 18, 2006

Publications

► Full Reference: Frison-Roche, M.-A., "Proposition pour une notion : l’opérateur crucial" (Proposal for a notion: the "Crucial Operator"), D. 2006, pp.1895-p.1900.

____

► Article English Summary: The market is conceived as having two kinds of actors: operators and regulators. But we can suggest a third term: the crucial operator. This notion, proposed here, assumes that the sector cannot function without it. It could be a network manager or a systemic company, the failure of which produces a domino effect, or a structure that maintains a system like the financial market companies. These kinds of "second-tier regulators" then have more rights and more obligations. They are either holders of essential infrastructure, or bearer of capital innovation, or centralize system risks. The regulatory systems should be rethought by integrating these "crucial operators".

____

____

► More developed Article English Summary: Competition Law neutralizes economic agents who act on the markets, by the rule of capital neutrality. Thus, the company is a transparent legal concept, which erases the specificities of organizations. Public enterprises are therefore only considered as an enterprise and the notion of "national champion" is rejected.

To escape this neutrality, without falling into the arbitrariness of the States against which Competition Law rightly fights, there is great interest and relevance in developing the concept of crucial operator.

The idea of a crucial operator is to no longer think of it in a neutral way, not in relation to its capital or those who govern it, but in relation to its market behavior. In fact, cruciality can be defined as the quality of an organization which puts in its dependence the efficiency and the good functioning of other organizations. In this, cruciality is the opposite of competition, which postulates that the company not only does not depend on others but also will seek by nature to harm it by appropriating demand to the detriment of its competitors. But it may happen that the market cannot be satisfied with the aggressive mobility that is competition and supposes the stability and support of others operated by the crucial operator.

This is so when the operator is the manager of an essential infrastructure since the other operators depend on it. This is also the case when the operator is the bearer of market innovation, which justifies access rights under essential facilities or agreements to produce research. The third case is when the operator carries the risks of the system, which explains why banks and financial institutions are most often crucial operators in that they carry the systemic risks of the banking and financial system. It is thus measured that the public or private character does not interfere in the qualification of crucial operator any more than the monopolistic character or not of the operator considered.

The consequences of such a qualification as a crucial operator is that the operator must have more obligations than an ordinary operator. Thus, the infrastructure manager has the obligation to open it to third parties, even though control usually generates a power of exclusion. Similarly, financial or insurance institutions, because they must prevent risks, will be obliged by specific prudential standards. But the crucial nature of the operator gives him rights but also powers. This is how market companies, operators of private law who hold the places, have a disciplinary power of exclusion that some have compared to the power of the State.

What is more, the crucial operator then appears to be a "second tier" regulator. Indeed, according to a pyramid figure, ordinary operators are subject to the disciplinary power of crucial operators who themselves are governed by public regulators, who are the first rank regulators. This quality of second-level regulator obliges the operator to behave towards his competitors with the same virtue as that which characterizes the regulator and first of all impartiality. This is the case with non-discrimination in accessing the network from its own competitors. In addition, a regulator must be accountable and behave in a transparent manner, while the ordinary operator is not subject to this principle, since competition law does not require transparency of structures and behavior. This link between regulation and governance clearly applies to financial operators, but it is also observed with regard to network operators.

We thus measure that if positive law, giving form by a last effort of vocabulary to established rules, recognized the existence of the notion of crucial operator, it would better identify this intermediate category between the ordinary operator and the regulator, because the crucial operator is a company, entering into the game of supply and demand but it also supports the stable structure of the market and the stability of this market, which is not the usual aim of companies.

________

Oct. 20, 2003

Organization of scientific events

June 11, 2003

Thesaurus : Soft Law

Référence complète : Larcher, G., La situation de La Poste dans la perspective du contrat de plan en cours d'élaboration et sur les mesures à prendre pour lui permettre de relever les défis qu'elle a à affronter, rapport d'information du Sénat, 11 juin 2003.