One question on the Law

LAW AND HISTORY : If the assertion of the law as "spirit of a people" is true, what practical implications should we draw?

It is therefore necessary to take the statement for granted: the law expresses "the spirit of a people." We want to believe, since Savigny stated it

It is therefore necessary to take the statement for granted: the law expresses "the spirit of a people." We want to believe, since Savigny stated it

Following the great author does not avoid explaining the meaning of such a statement. Expressing the historical conception of law means that all legal events are the result of a culture of a "people", which has been built over the centuries. Thus, because a French "people" are, there is a French law that reflects this.

If this is true, then the implications of this fact are considerable. First, in order for a law to be effective, coherent and applied, it must correspond to the "spirit" of the people to whom it applies. The legislature and the courts must make it part of their art, not to rush a historical movement, do not ignore it,but to adopt the pace. Therefore, foreign legal techniques cannot be welcome.

The most important sources of law are the most spontaneous, that is to say, those in which people forge through the centuries of usage and customs. The law written on a white sheet of paper is a mistake, unless it is itself covered by a long period after.

The legislator and the judge should have taken to the method of knowing the spirit of their society in which they move: the sociology and history cease to be ancillary to become positive law. In this, the common law rooted in its "stare decisis" better expresses this conception than does the system of Civil Law.

But more importantly, there has to be a "people" whose mind law would collect. As rightly pointed out by the German Constitutional Court in 2009, there is no "European people". So how can we build Europe? While the French, British, German, Italian, Spanish, peoples etc. have such a different mind, and that expansion now brings us to the Slavic soul?

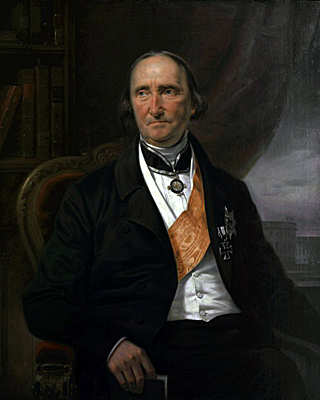

The assertion of "the law is the spirit of a people" is not indisputable but it is very famous. It is due to the great German jurist of the early nineteenth century, Friedrich von Savigny.

Professor of Law, known by so many titles, especially because he contributed to the construction of the private international law and that he opposed welcoming the Code Napoléon in Germany, Savigny is considered to be one of the founders of the historical school of law.

In this school of thought, the law comes from a people, expresses its culture, history and the "spirit" of it. Thus, if the history of it is the idea of a Nation, or even the idea of the State, then the law develops consubsantiel links with the State, not so much because it would have an ontological relationship with it, but because the facts have built throughout history an intimate relationship between Law and State.

To take one example, in Germany and France, which probably are two "State-Nations", the law couldn't then be distinguished from the state, whereas in the United States, because of the way their history was made, the law cannot break away from the idea of a Constitution, and its guard, namely the Supreme Court.

By ensuring this, when we fight without doubt the state or judges, one could say that everyone is right, whether this is in France, in Germany or in the United States, these laws don't express the same "spirit of the people.". They aren't able to inderstand each other, neither are they able to agree.

If the general assumption is true, and that is sustainable in any case, then the law is a technique that can claim to master without knowing anything about the history of the people to whom it applies. For example, to be familiar with the North American law, one must know the history of the American people, if we don't want to make technical legal mistakes. Thus, one can understand the persistence and scope of the constitutional right to own and bear guns if one refers to the history of this country. Similarly, we can not understand and therefore handle well the current French law, if nothing is known about the French Revolution whose thinking remains active in the present French law.

This affects what the lawyer has to learn. He must not only learn the "positive law", that is to say, the binding laws. He must "understand the mind of the people," if the law is to be its expression. But how to know this mind ? The lawyer must delve into history, must join in the life of the city, should be concerned with sociology. The design technician studying law during which one learns that the law is not conducive to that.

But, never mind, if the assertion is correct, the implications are broader still.

Thus, one who writes the laws and judgments, must first be modest. Indeed, for the adherents of this historical school of law, the most precious source of law is neither the bill nor the judgment, but all practices voluntarily adopted by the social group and refined by the passage of time. If one believes that the law expresses the spirit of a people, he must adhere to legal pluralism and stand back from the legicentrism. The attention is paid to customs, the social way of doing things.

This is certainly the conception of Doyen Carbonnier, a great legislator and yet a modest legislator, for whom "Le droit est seulement le vernis à la surface des choses (the law was only the polish on the surface of things)" and for whom uses and customs are primarily law. In Germany, the country of Savigny, the custom is recognized officially as a source of law.

This seems to move towards a truism that there is a "French people" which gives a "French law"; there is an "Italian people" which gives a "Italian law"; there is a "German people" which gives a German law ", and so on. It sounds acquired.

But it is not.

Indeed, isn't it possible to have a people not having the same dimensions as the law ? For example, smaller than the law ? Or on the contrary a law larger as a peuple ?

your comment